The first years are so important because so much of school builds from those early periods – handwriting and learning maths and learning to write. It’s so important for kids to feel like that there's someone in their corner. And that can definitely be teachers and the school.

Starting School

Autism resources for educators

Starting school is an exciting time for students and teachers alike. Along with getting to know your new students, you might be thinking about new spaces, routines and experiences in your classroom. These resources aim to help educators of students on the autism spectrum (diagnosed or undiagnosed) prepare for the first year of schooling. Explore:

- practical ideas to help students adjust in your classroom

- how to build relationships with families and have a positive dialogue with them

- strategies from other educators and experts about inclusive practices

- perspectives of autistic individuals and families of autistic children.

The term ‘neurodiversity’ is often used to describe the natural variation in the way an individual’s brain functions. It refers to the differences in the way people behave, and how they experience, understand and interact with the world around them.

As each individual is different, the term ‘neurodiverse’ applies to everyone, including 'neurotypical' people. The term ‘neurotypical’ simply refers to a person with a more common type of brain (also known as a neurotype) in terms of how they sense the world and people around them, and how they think, feel and respond. When you are neurodivergent, you differ from the from the ‘typical’ or more common type of brain. Autistic people are neurodivergent, as are people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or with learning differences such as dyslexia or dyspraxia. About 1 in every 5 or 6 children has variations in their brain development (raisingchildren.net.au, 2022).

Notes on language

When referring to neurodivergence, disability advocates encourage the use of inclusive and non-judgmental language. Some disability advocacy organisations suggest that person-first language (for example, ‘a student who has autism’) is the preferred way to address disability. Research indicates that a large proportion of the autistic community prefer identity-first language (for example, ‘an autistic student’). It is helpful to speak to a student’s family about their preferred choice of language rather than making any assumptions.

This resource uses both person-first language and identity-first language. We acknowledge that individuals choose how they wish to be identified.

No two students on the autism spectrum present in the same way. Autism is described as a spectrum, which means that individuals are likely to have a different profile of strengths and needs in various areas of functioning.

Signs and behaviours of autism are often present before the age of 3. However, characteristics of autism may not be detected until a child starts primary school. Young children may experience difficulties adjusting to the school environment and new social situations. The transition to school might feel quite overwhelming for the child.

Some of the indicators of autism might include delays in communication, narrow interests, lack of social interaction or interest in other people (which may include reduced eye contact with others), emotional regulation difficulties, sensory sensitivities and repetitive behaviours.

Autistic students may also present with exceptional strengths, which can be incorporated into learning activities at school. Common strengths include:

- strong visual skills and ability to pay attention to detail

- problem-solving and logical thinking skills

- memory skills

- hyperlexia (ability to decode written language at an early age)

- good understanding of and adherence to rules

- special interests in particular topics

- ability to focus and pay attention for extended periods

- exceptional honesty, reliability and loyalty.

In some cases, an autistic child may also be diagnosed with another condition. When one or more conditions occur together, they are referred to as co-occurring or co-existing conditions. Co-occurring conditions are more common in neurodivergent children than in the general population and can be present from early childhood or may not present or be diagnosed until adolescence or adulthood.

Some common co-occurring conditions seen in autistic children may include language delay speech disorder and developmental language disorder, anxiety, ADHD and motor difficulties. Find out more about conditions that can occur with autism.

Not all autistic students have or develop a co-occurring condition. However, if you notice a behaviour change, a regression in their skills, or feel they are not responding as expected to the supports in place at school, it is important to discuss this with the student’s family. The family may have noticed similar behaviours at home. Discussing your concerns with the family will help you to make appropriate adjustments to help the student access learning at school. You may also recommend that the family follows up with a health professional if the student seems to be showing signs of another undiagnosed condition alongside autism.

The term ‘twice exceptional’ is used to refer to individuals who are both neurodivergent and gifted. Twice-exceptional students are likely to perform inconsistently at school, presenting with uneven skills and asynchronous development (that is abilities that are developing at different rates). Having an awareness of twice-exceptionality may enable you to help these students to succeed at school.

Characteristics

A twice-exceptional student may demonstrate:

- significant creativity in one or more areas

- hyper-sensitivity to sounds, tastes, smells, etc

- perfectionistic traits

- superior critical thinking and problem-solving skills

- strong sense of curiosity

- high-level abstract thinking

- difficulty with the development of early reading and writing skills due to deficits in cognitive processing

- low self-esteem

- underdeveloped social skills

- strong ability to concentrate deeply in areas of interest

- behavioural issues due to underlying stress, boredom, under stimulation, or lack of motivation.

Adjustments

Teachers can support twice-exceptional students by making adjustments that acknowledge their individual learning needs. These can include:

- nurturing their strengths and interests, using their strengths to plan learning and teaching sequences

- supporting their social and emotional development

- identifying gaps in their learning and finding ways to support any relative weaknesses.

Every young person with autism has very different strengths, and so each one of those young people need to be recognised and acknowledged for what it is that they can bring to their schooling life, to their peers, to their teachers, and to their communities.

If you believe a student is showing signs of being neurodivergent, it is important that you first discuss your observations with the school support team. Collectively, you can decide on the best way to raise your concerns with the student’s family. Your discussions with the family must focus on observations of the student’s presenting behaviours, challenges and strengths, and ways you might support the student at school. Focusing on observations opens the way for transparent conversations around topics that families may find sensitive.

Importantly, as an educator, you are not qualified to, nor are you expected to, diagnose a child with a disability. However, you and the school support team may impute that a disability exists in one of four categories: physical, sensory, cognitive or social/emotional. This means you believe, based on reasonable grounds and supported by documented evidence, that the student has an undiagnosed disability as defined by the Disability Standards for Education 2005 that has a functional impact on their capacity to access and participate in learning on the same basis as their peers. For more information, go to the 'Schools' obligations to students with a disability' topic below.

The school support team may determine that there is a need to provide further supports for the student. Before making any educational adjustments, it is advisable to meet with the student’s family to discuss your concerns and to co-plan appropriate adjustments. The family could display mixed emotions in the meeting. They might feel a sense of relief that you share their concerns, or it may come as a surprise to them that their child is not adjusting to school as expected. For more information, go to the 'Discussing observations' topic below.

More information and guidelines about the assessment and diagnosis process can be found on the Autism CRC website.

In some instances, the family may not engage with the school about the need for educational adjustments or not agree with the school’s observations regarding the student. In these cases, it is still in the best interests of the student to support their learning in the most appropriate way, as determined by the school support team. The school must still make reasonable adjustments to support the student to access education on the same basis as their peers.

Further information

A national guideline for the assessment and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders

Autism diagnosis for children: a guide

Supporting children with neurodiversity

Thinking and learning strengths in autistic children and pre-teens

Imputing disability for the NCCD

Topic resources

Indicators of autism [PDF]

All students are entitled to access and participate in education. A disability should not be a barrier to that access.

The Disability Standards for Education 2005 (also known as ‘the Standards’), and the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA), require Australian school students with disability to be provided with the same opportunities at school as other students. This applies to all students with disability.

Watch the NCCD 'Disability Standards for Education' animation to learn more.

The Standards explain the obligations of schools to provide access to education to students with disability on the same basis as their peers. The Standards cover the following five areas:

- enrolment

- participation

- curriculum development, accreditation and delivery

- student support services

- elimination of harassment and victimisation.

The Standards clarify the obligations of schools under the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA). Under the Standards, schools must do three things:

- They must consult with students with disability and their families.

- They must make reasonable adjustments to help students with disability.

- They must ensure students with disability are not treated less favourably than students without a disability.

Reasonable adjustments are the ways in which schools support students with disability. Reasonable adjustments are measures or actions taken which help students take part in education on the same basis as their peers.

The adjustments provided to a student are determined by their needs and may include adjustments to the curriculum, equipment, and physical and human resourcing requirements. Some examples include:

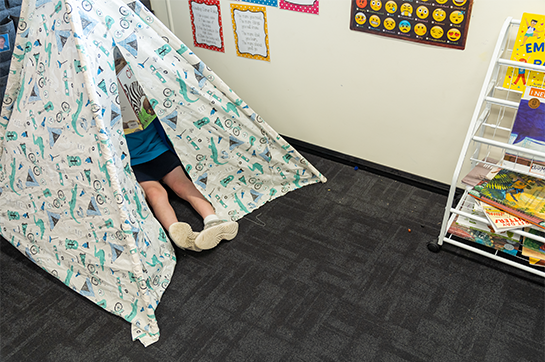

- modifying a corner in your classroom into a quiet space

- creating visual schedules of your classroom routine

- differentiated learning activities

- access to learning support programs.

Schools can help to meet their obligations under the Standards by:

- creating and implementing inclusive policies and procedures, for example, developing inclusive spaces in classrooms to accommodate the needs of all students

- ensuring all staff complete professional development on disability awareness, rights and obligations, for example, providing professional development opportunities in working with children on the autism spectrum for all staff.

The Disability Standards for Education e-learning provides self-paced professional learning for educators to develop their understanding of the Standards in this area appropriate for their individual role.

Important considerations

Remember, schools have an obligation to support all students with disability under the Standards and the DDA. The Standards can also help support families and their child to have fair and accessible consultation when it comes to their child’s schooling.

- Communication and consultation with families are key, including using information provided (such as observations and transition statements) by families about the student.

- Consult with your support staff, the student and their family to implement reasonable adjustments to support the student.

- Observe the student in your classroom and communicate regularly with the student’s family.

Further information

Explaining the Disability Standards for Education

The Disability Standards for Education in practice: Action plan

Understanding the Disability Standards I

The Disability Standards for Education II: Making reasonable adjustments

Disability Standards for Education: A practical guide for individuals, families and communities

There is evidence of a strong link between feeling positively connected to school – where children feel accepted, respected and included – and a range of outcomes such as academic success, high self-esteem, positive affect, optimism, hope, life satisfaction, and positive long-term life outcomes. A sense of belonging and connectedness at school supports an inclusive school culture. Schools that build supportive classroom cultures establish positive learning experiences for all students throughout their schooling experience. Using inclusive teaching approaches such as Universal Design for Learning will engage and support the needs of all learners in the classroom, including autistic students.

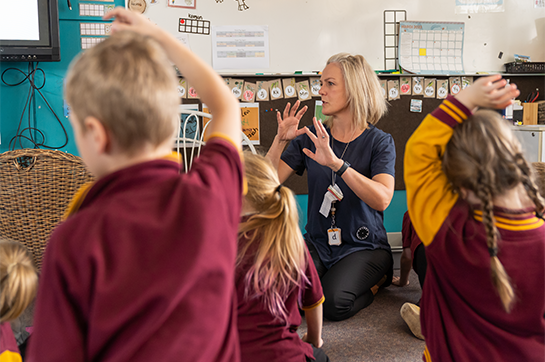

When teachers are inclusive for autistic students, they're inclusive for everybody.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a comprehensive framework that is used to support teachers to address diversity of learning in the classroom. It was developed by researchers at the Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) and is based on decades of neuroscience research, leading to the understanding that learners are different in many ways and need a range of teaching approaches and resources to be successful.

UDL supports teachers to design learning environments and teaching approaches that are accessible for all children. The guiding principles of UDL support you as a teacher to set learning goals and plan curriculum-based activities, assessment, teaching strategies, and resources to meet individual learning needs.

The UDL framework has three guiding principles you can use to provide multiple ways of engaging children, representing knowledge, and demonstrating understanding.

As teachers, working with children in the first year of schooling, knowing your students' strengths, challenges and interests helps you to identify multiple ways to motivate and engage students in learning.

Young children with diagnosed or undiagnosed autism may have differences or difficulties socialising and communicating with other children. They may have particular interests and fixations on topics and are likely to have sensory needs that impact on their participation in the first terms of school. For example, children may be frightened of loud noise, may find bright lights overwhelming, or they may get anxious with large groups of children. These sensory issues do not mean that the child cannot learn and participate in the classroom, but they may have an impact on their learning if not addressed.

You can make a positive difference in the early education years by providing multiple means of engagement in the classroom.

How might this look in a classroom?

- Provide choices in learning activities and topics, or where and how children learn.

- Find out what your students are interested in and be flexible in how you engage them in the curriculum.

- Structure learning by breaking down the steps. Use visual prompts to support students to understand and follow expectations.

- Support the sensory needs of autistic students. Develop an understanding of the range of sensory needs that they may have.

- Provide options to use: noise-cancelling headphones in some noisy environments; eyeglasses, sunglasses or hats for areas with bright lights.

- Recognise behaviour triggers early. If students become anxious, they may need to move or fidget with an object or tool of their choice.

- Provide responsive spaces for students who need a safe and calming space at times due to sensory overload, anxiety. These types of spaces can also provide stimulation for students who need to be active with their hands, body and feet.

- Have discussions with your student’s family about possible behavioural triggers that indicate the students need to have time and space to be calm.

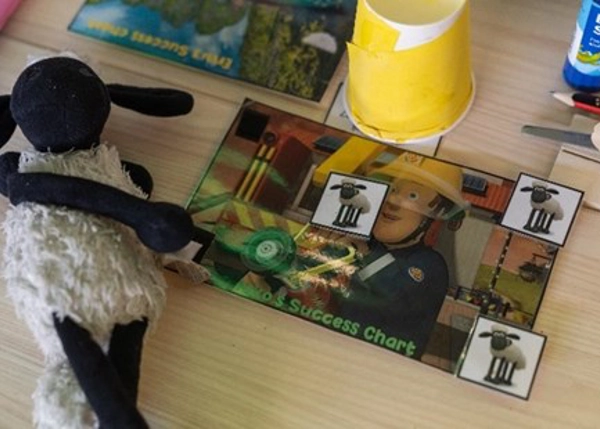

Create a reward chart based on the student’s interest.

Provide students options if they need to fidget with an object.

Representation refers to the ways that educators present information to children. Neurodivergent students need to be able to access and understand the information presented to them. Students in the first terms of school will benefit from structure, routines and explicit instructions that meet the needs of children on the autism spectrum. You might find these strategies good for the whole class.

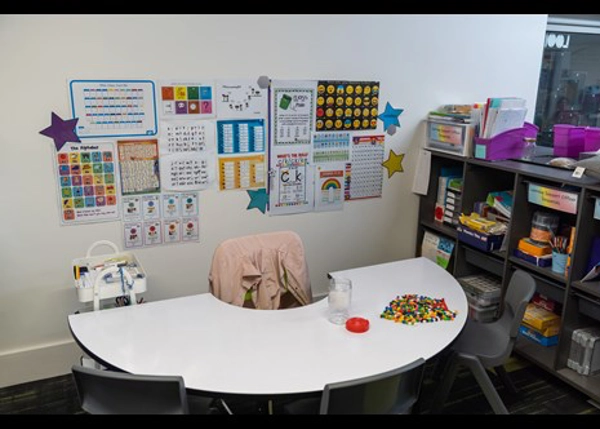

Create and display visual schedules for students.

Concrete materials support learning abstract concepts.

How might this look in a classroom?

- Use visual strategies or structures to present information, support timetabling and scaffold instruction and learning. There are many good ideas here to support you to use visual schedules in your classroom.

- Organise the classroom with visual prompts to colour code resources and help students navigate learning tasks.

- Use different approaches and teaching techniques, such as role-modelling to practise behaviours and skills.

- Use explicit teaching, concrete materials, independent learning and peer support for addressing learning needs.

- Embed supporting social communication and building peer relationships in classroom learning and playground support.

- Scaffold activities for students by breaking activities down into manageable steps and provide supplementary resources to support learning.

- Be aware of your language and communication, such as pace and choice of words.

- Make use of digital technology including interactive and assistive communication devices.

Offer students different options to demonstrate what they know and what they can do. Supporting students with different opportunities to use their strengths and to engage in the classroom can make a positive difference. Providing students with choices in how they communicate and interact with class activities and each other will ensure a more inclusive and successful environment for everyone.

How might this look in a classroom?

- Plan the use of flexible assessment, such as additional time, and adjustments, such as technology and quiet space.

- Support students with organisation to start, continue and complete tasks.

- Provide alternative ways to communicate, such as hand signs, images/symbols, and augmentative or assistive technologies.

Not every classroom is specifically designed to respond to the needs of all students. There are simple changes that can be made to make the classroom environment a comfortable and calming space for all.

What simple changes could you make to make your classroom a more inclusive space? Audit your space with the Assess your classroom environment tool.

Building trusting relationships with students and their families takes time and is based on mutual commitment. Such relationships have benefits for everyone as they:

- increase shared knowledge of student diversity and individual differences

- support two-way dialogue about the reasonable adjustments provided in response to the students’ requirements, strengths and aspirations

- strengthen effective communication and other ‘soft’ skills (for example, active listening, empathy, compassion)

- lead to effective teacher–parent partnerships for collaboration

- facilitate the child’s move to the new school and classroom

- support the child’s peer interactions, with teacher guidance

- improve the students’ wellbeing at school

- help to prevent stressful situations that can trigger anxiety for teachers, students and parents.

What are some things to consider when developing a trusting relationship with a student on the autism spectrum?

-

Find out about the student’s strengths and interests.

-

Find out about the student’s sensory preferences and sensitivities.

-

Observe the student in their interactions with peers and adults.

-

Schedule brief and regular activities that draw on the student’s topics of interest.

-

Use visual aids (photos, objects, videos) to support discussion with the student.

-

Ask the student about their favourite activities at school.

-

Show interest in their activities after school.

-

Use a communication book or learning portfolio with sections on ‘What I have learnt’, ‘What I tried hard to achieve’ and ‘What I need support with’.

-

Encourage the student to take on roles in class with your gentle guidance.

-

Express in explicit ways your pride for their hard work, effort and curiosity for learning.

-

Establish a plan with the child and their family about when and how to take breaks.

How can I support these students in their schooling experience in the community?

-

Make a list of the community places your students visit often with their families.

-

Drawing on that list, plan for community activities throughout the year related to the Australian Curriculum.

-

Create social stories about familiar community activities.

-

Practise behavioural routines and expectations in the classroom to prepare students for community contexts.

What can I do to build a relationship with the families of autistic students?

- Send a personal email to families introducing yourself and your teaching philosophy and your values, emphasising your high regard for effort and resilience rather than performance.

- Offer options to communicate with you: by email, phone, in person, communication book.

- Schedule sufficient time for meetings with specific discussion topics.

- Acknowledge families as the experts on the child.

- Use active listening in your spoken communication.

- Have an observer in meetings with families to reflect on your communication skills, and be receptive to their feedback.

- In your communication with families, show genuine interest in their child’s daily life, their habits, interests and hopes for the school year.

- Take notes on what has worked really well and what did not.

- Talk about activities within the school, seeking to understand their concerns and expectations.

- Talk about activities in the community, aiming to support their child’s equal participation in these events.

- Express your interest in meeting with any allied health professionals that support the student so that you can use similar strategies for engagement and learning.

- Invite constructive feedback as part of your self-reflection as an educator.

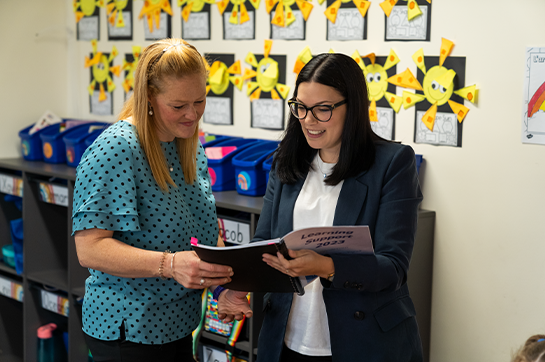

The parent brings that unique expertise that the teacher doesn’t have. And for the teacher, it’s important in that very first meeting to really acknowledge that expertise that the parent brings, because then that creates a really nice foundation for them to communicate and share the power of knowledge.

- Social learning is as important as academic learning. Both form part of a holistic learning process.

- Heightened anxiety in students reduces their capacity for social participation and therefore affects their learning.

- Intentional and systematic observation of students’ responses to activities is a key step for effective teaching.

- Monitor social interactions with peers to check that students are not being bullied or excluded from activities.

- Use the students’ interests to teach them new skills.

- Spend time familiarising the students’ peers with their ways of working and communication system or approach.

- Support students’ peers with opportunities to work together in pairs or groups with students on the autism spectrum.

- Schedule time for reflection on learning activities with the student to guide self-regulation.

- Create a circle of trusted peers with shared interests for specific group activities.

- Schedule time for mindful body-awareness activities.

- Create a visual aid to help the student keep track of their progress towards achievement of big social or academic goals.

- Set up a work system for learning activities that sets out the steps to be completed, the materials required, highlights the completion of activities and states what happens next.

- Set up routines with embedded visuals for unexpected changes to the routines.

- Organise whole-class activities to raise awareness of human diversity (including autism).

I like educators to be aware that parents give you their child with great trust, it's a privilege. We are given people's centre of the world for six hours a day. It's a trusting relationship.

As an educator, making observations of student behaviours is an important step in building your knowledge of the student and establishing a positive relationship with them. Planning time for observations is good practice, and observations can be conducted by you or in collaboration with other professionals supporting the education and care of the student. When observations are made and recorded regularly and consistently, they offer valuable information to inform successful practice.

Making observations:

- offers valuable information about the student’s strengths and abilities

- enhances knowledge of suitable supports for the student

- develops understanding of the student’s emerging skills

- illuminates the events and student’s needs that are driving behaviours, such as stimming or hand flapping

- monitors social interactions with peers

- informs personalised planning

- creates a sound basis for a constructive discussion with the student’s family and other professionals.

Observations are most effective when they build a profile of student interactions in a range of environments, and in formally structured and unstructured activities. You should take advantage of every opportunity to observe the student interacting with peers and familiar adults during a range of planned and unplanned learning activities and events.

Making and recording observations can be a manageable and effective method for collecting information if it is planned thoughtfully. Observation sessions can be informal, targeted and short. Consider their use – there is little point in making a long video recording if you do not have the time to review it. To make this process easy and accurate, you can use a variety of tools such as:

- digital or print observation guides

- audio/video recording devices

- photos of activities

- students’ artefacts

- students’ drawings.

Before recording digital images, check your school’s policies regarding recording, usage and storage of digital images of students.

Educators can use consistent and accurate observation records as evidence for developing student learning and behavioural profiles.

Drawing on your knowledge of student development and behavioural expectations in school, you can develop student learning profiles targeted to your students’ needs. Your observations can form a basis for attributing student characteristics to differences requiring further attention from an expert team. In addition, you can draw on these observations in your communication with school leaders and allied health professionals to seek input on suitable additional learning or behavioural supports for your students.

As an educator, you cannot make a diagnosis. You can share your observations with families to help them in seeking further support from other professionals or a diagnostic team.

Good observations are really, really important because there is no point in having a meeting with a parent if you haven't got [any documented] observations, and all of a sudden you're having a conversation and the parent might say, 'Well, what are you talking about? Give me an example.'

An observation guide is a tool to organise your information and help you when discussing your observations with the student and their family. Your school or system may have their own tools for recording student observations, or you may wish to use the Observation guide. Consult your school leadership regarding policies that determine what information can be shared or distributed. The guide is arranged in topics to help you consider the supports you could put in place for the student. All students are different, and the topics and questions are simply organisers. Complete only those sections you need to guide your discussions.

You can use this guide in your conversation with families to discuss the behaviours that can be prioritised as teaching goals, and which supports might be appropriate for achieving these goals.

Further information

Autism first signs: a checklist for primary school age children

Topic resources

Observation guide [PDF]

As educators, meeting and working with families will build a more comprehensive picture of a child’s learning characteristics and behaviours. Drawing on your observations, your conversations with families can lead to informed evaluations and timely contacts with school staff and allied health professionals.

Effective communication with families is dependent upon respectful engagement and listening with an open mind. Discussions about students should be positive and strengths-based, with a focus on collaboration and solutions.

Having and maintaining a positive dialogue with families is central in supporting your student. Successful partnerships between families and educators enables positive outcomes for students.

- Make a plan for engaging with families before school starts.

- Send a welcome message (in person, by email, by phone).

- Offer manageable options for communicating formally and informally.

- If possible, organise the first meeting to be in person.

- Ask how they would like their child to be involved in discussions.

- Discuss their aspirations for their child for the school year.

- Plan a follow-up meeting or phone call.

- Check if the family has any support needs which need to be accommodated during the meeting, such as a interpreter or cultural liaison person. Many families of neurodivergent children are themselves neurodivergent and might have preferred ways of communicating.

- Encourage the family to bring a support person or an advocate to the meeting to support them, or speak for them if they wish.

- Ask if the family have any concerns they wish to discuss.

- Organise for no more than 2 professionals to be present in the meeting to help create a supportive atmosphere.

- Set up a distraction-free space for the conversation (for example, a meeting space away from the classroom).

- Arrange furniture so that participants have a choice about where they sit during the meeting.

- Use your observations to highlight key points for one or two topics that you wish to discuss.

We really have to think about the communication preferences of the families as well and understand that there are many different preferences, particularly if they are autistic or neurodivergent. So the same way that we understand and provide accommodations for children, we must also provide accommodations and understanding for our families who may also be neurodivergent themselves.

- Allow time to introduce all participants and settle into the meeting.

- Acknowledge your shared intent to seek the best for the student.

- Start the conversation with a focus on the student’s strengths.

- Explain the intent of the observations and the type of information you have gathered (the what and the why). If you have shared the observation guide, ask if there are any terms that need explanation.

- Ask the family about their support need.

Things to remember throughout the conversation

- Focus on the key concerns arising from your observations.

- Ask questions.

- Listen to the ideas participants bring to the discussion.

- Paraphrase their ideas to confirm your understanding.

- Be brief, clear and concise when describing a behavioural issue.

- Use your observations to illustrate the issues you are raising.

- Provide easily understood information in small increments.

- Allow time at the end for additional questions.

- You may find the conversation brings up other concerns. It is important to stick to the point of the discussion. Note any additional concerns and confirm those that you can follow-up.

The tips for successful meetings pdf provides more suggestions.

- Give practical guidance about next steps using evidence from your observations about what is working well.

- Emphasise the value of a positive school–family partnership.

- Provide communication options and ask families what they would prefer.

- Suggest and confirm how often you will meet.

- Clarify additional topics agreed to be followed up and by whom, and set reasonable expectations of when this will happen.

- Arrange for a check-in with participants to ensure they feel listened to and supported.

Ask about:

- any family or cultural practices you need to take into account

- languages used at home

- daily family routines

- activities each family member does with their child

- activities the child does with siblings or play companions

- methods they use to attract the child’s attention, how they praise their child and how they help calm their child

- their views about learning and progress

- their aspirations for their child's schooling experience.

- Make a positive start by highlighting the child’s skills and strengths.

- Discuss your observations about the emerging skills (what the child can do with help).

- Ask questions about food and drink routines at home.

- Discuss how self-care is modelled at home.

- Show how objects and photos can help the child follow sequences of steps.

- Ask about communication preferences used at home and in the community.

The Discussing self-care pdf provides more suggestions.

Both educators and families can work together to support the child through positive discussions. The Conversation guide for educators pdf provides a list of topics and question prompts you can use when talking to the child's family about your observations you recorded in the Observation guide pdf which you can use to document your observations of the child. In taking a child-centred approach, you will be able to draw on the knowledge families have of their child and ensure productive discussions with them.

A communication book (in printed or digital format) is a way you can share important observations with families each day. You can let them know what worked well for the child that day, and any difficult moments the child experienced. It also allows educators and families to track student progress over time.

Families could also use the communication book to let you know any concerns they have about their child, and anything you need to know about their child’s wellbeing.

Topic resources

Tips for successful meetings [PDF]

Discussing self-care [PDF]

Conversation guide for educators [PDF]

Observation guide [PDF]

Students adapt to the school environment differently. Change can be stressful for most students, so it is important to closely monitor your students’ transition to school. You may find that a student who initially experienced some difficulties getting used to being at school becomes more comfortable with familiar routines over time. However, they might find changes to a ‘typical’ school day a bit more challenging.

A child’s family can help you understand how to support their child both on a typical day, and when unexpected events occur. Having a way to communicate that something new is going to happen will help set the student up for a positive day.

If you suspect that a student might experience difficulties with an upcoming event or change to the usual routine, it is important to communicate with the student’s family beforehand. Advance planning and preparation can help to make the change in routine more manageable for the student.

Common events that may take place at school

- School assemblies

- Themed dress-up days (such as Book Week parade)

- Sports days and carnivals

- Cultural and religious events, festivals and ceremonies

- Incursions (for example, visiting mobile farm, visiting performers)

- Special visitors to the school (such as parents’ days, guest speakers)

- A new adult in the classroom (for example, relief teacher, education assistant, class helper)

- Events that involve food (such as class parties, ordering food from the canteen, cooking activities)

- Combined class timetables (perhaps due to weather, special activities)

- Immunisations

- Practice fire drills

- Building works

- Specialist lessons in different parts of the school (such as physical education)

Events that may occur away from school

- Excursions (for example, museum, concerts)

- Visiting places in the local area

- Sports events (for example, inter-school sports carnivals, swimming lessons)

- Periods of remote learning

- School camps or trips

Note: Some of these events might be considered part of the normal school routine in some schools and may require moving to a different space in the school or involve specialist teachers or visitors.

Each student reacts differently to changes in routine. Different occasions at school can make some students feel nervous or uncomfortable. The way individual students respond at different times can also be influenced by other factors (for example, fatigue, social or sensory demands). For some students, even what seems like a small change in routine can be unsettling, while for others it is larger changes that are challenging. Moving from one activity to another, or leaving a task unfinished, can also make some students feel unsettled. Not all signs seem like a negative change but can still indicate stress. Here are some common examples of signs of stress to look out for:

- Unexplained illness (such as complaining about a stomach-ache to be excused from activities)

- Unusual changes in behaviour

- Difficulties communicating what they are feeling

- Asking lots of questions

- Avoiding new activities

- Increased stimming

- Talking about their favourite interest more than usual

- Increased anxious behaviours, excessive worrying

- Complaining of fatigue more than usual

- Behaviours that are out of character for the student (for example, covering ears, hiding, running away, shutting down, shouting, refusing to follow instructions or school rules)

- School phobia (student can't attend)

- Refusal to move to classes or different spaces

Some events occur only once in a school year, for example, an off-site excursion or a district sports day. Working with the family in advance and preparing the student for these events can lessen the impact of the change on the student.

Supports and adjustments implemented to support the student if they feel overwhelmed by different occasions at school should be included in formal planning documents such as a behaviour support plan or an individualised learning plan. The plan should include strategies for the school to employ when the student encounters challenging new events at school.

Talk with families/support team

Communicate with the family in advance about upcoming changes in routine and ask if they feel their child might need some extra support. Invite the family to meet with the school support team early in the school year to plan for how to prepare the student for special occasions. This could include a discussion about:

- length of time that their child can tolerate being outside of normal routine with an option to attend a part of the event with a plan to extend attendance over time

- the student’s possible triggers (for example, heat, noise, crowds) and ways to support the student; keep a record of these for reference throughout the year, and provide this information to relief and substitute teachers

- suitable comfort and fidget objects the student can use at school

- how the student can ask for help or take a break, especially if they have difficulty communicating their needs (the student might prefer to make a signal when they are uncomfortable)

- developing a plan together to support the student when they feel overwhelmed

- provision of a quiet area the student can access

- other adults in the school who can support the student (for example, education assistant, counsellor, sickbay attendant, office staff)

- how to communicate about the student’s needs (for example, phone call, email, a communication book sent between home and school, an app, a shared collaborative electronic document, or through the school portal or learning management system).

Discuss with the family how you might be able to talk to other students in the class about the child’s support needs (for example, triggers and possible response to triggers). Consider how a student might benefit from:

- specific roles or responsibilities to give ownership or some control over an otherwise unfamiliar event, for example, completing a task for the teacher that provides a movement break

- opportunities for choice (something as simple as options for where to sit can help).

Arrange a follow-up conversation with the family following events to discuss any support modifications for future events. Ideally, arrange to meet with the family regularly to discuss any changes in their child’s support needs.

Prepare the student

- If appropriate, visit a new location in advance to become familiar with the new environment.

- Let the student know in advance if there is going to be a change in the usual routine. Reassure them that most children feel a little nervous when they experience new situations at school.

- Use a visual planner to explain what changes in routine are likely to happen.

- Create a social story showing what the event or situation might look like for shared reading with the class.

- If the activity is likely to recur (such as a school assembly), agree on a place the student will always sit and where their support person will sit.

- Roleplay elements of the event, for example, getting a drink of water (with supervision if required), finding the toilets, going to the bus, eating lunch.

- Pack a bag with calming objects, headphones, hats, sunglasses or colouring-in activities for the student.

- Practise breathing and relaxation strategies they can use, like finger stretches or five-finger breathing.

- Practise how the student will communicate if they are feeling overwhelmed or need support.

- Visit a quiet space that can be accessed during the event, and provide them with an exit pass, take a break card or help card they can show a teacher if they need a break (some schools put this on a lanyard that the student can wear around their neck).

- Offer mentoring and support from older students or peers (such as a buddy system).

- Talk with the student about upcoming changes in routine and plan what support they might need.

- Ask the student what they might need or want if they feel overwhelmed.

- Plan regular breaks during the event so that all students can recharge and can regulate their feelings with or without support, as required.

Planning guides

The 'Planning for change: Educators' pdf can be used as a prompt to guide discussions with a family about a student’s support needs for different events. Alternatively, you may prefer to invite the family to provide advice using the family version of the change planner.

Emotions impact student behaviour in a range of ways. Young children on the autism spectrum are still learning to notice and recognise their emotions, so they need more support to manage their emotions and behaviour. Challenging behaviours tend to occur when young children are not coping with their emotions or when they become overwhelmed by what they are being expected to do or the demands of the environment. This means that the way people are communicating with them can either support a student or increase their stress and distress. Sensory experiences can range from enjoyable to highly distressing for young children, even when they are not able to name how they feel.

Something to really keep at the forefront of your mind is understanding that children do the best they can, when they can – they're not intentionally, for example, engaging in challenging behaviours. There's always a reason for behaviour.

Emotions tend to be related to experiences, social needs and personal wants. Emotions are complex brain and body states that involve three distinct responses:

- An experience results in body and brain responses usually followed by an expressive response (behaviour).

- The body and brain response is what we normally call an emotion. For example, if something happens that makes someone happy, that feeling of happiness is signalled to the person through their body and brain responses.

- The body’s chemical reaction in most people will typically be the same but the body responses are more individual, with no two people feeling any one emotion exactly the same way. One person may feel happiness in their face and stomach, while another may feel it in their hands and face.

Spoon theory has become a very useful way of talking about energy levels, mindful body awareness and self-regulation. As described by Christine Miserandino, you can think about how much energy you have across the day in terms of the number of 'spoons' you have. If you start the day with 12 spoons, how many spoons will it take to enter a busy school playground or participate in a classroom activity? Those are the sort of questions we ask when we think about how to approach strategies of self-regulation. Once someone has used all their spoons for the day, they often end up overwhelmed, which can present as survival behaviours. Individuals can regain spoons by doing activities based on their interests, and engaging in preferred sensory activities.

Spoon theory can be used to help educators appreciate the different challenges and limitations that individual students may face, especially those with chronic illnesses or disability. By understanding spoon theory, teachers can better support and accommodate these students, and help create a more inclusive and understanding classroom environment.

Children – like most people – can become more stressed, distressed or overwhelmed when they are unwell, tired or hungry. For children on the autism spectrum, stress, distress or overwhelming experiences at school can be a problem. If a student is not able to recognise when they are becoming stressed, distressed or overwhelmed, they cannot take steps to calm down or self-regulate, potentially resulting in behaviours that are governed by their emotional brain or their survival brain. If children enter into survival mode repeatedly, this can alter their brain chemistry, resulting in even more dysregulated behaviours.

Triggers can include:

-

unexpected changes in routine or environment

-

unexpected transitions or being asked to transition to another activity or task before the child has finished what they are currently doing

-

sensory overload in loud, bright or cluttered settings

-

difficulty with social interactions and communication

-

overstimulation from technology or screens

-

unfamiliar or challenging activities or tasks

-

unfamiliar people or places, stress or distress due to a lack of object permanence leading the student to worry that their family, home or belongings no longer exist

-

limited access to sensory or emotional regulation tools or resources

-

unmet support needs in any area of functioning.

It is important to recognise that a student’s response may have been caused by a series of events, which may have started before they arrived at school, that have collectively built up resulting in what is sometimes called a ‘meltdown’. A student may not be aware or able to articulate the reason for their emotions or behaviours.

Working in partnership with the family to develop an understanding of a student’s triggers means that you can notice the signs that emotions or behaviours are escalating. You can then help the student by supporting them to regulate their emotions before they are overwhelmed.

Establishing a way that you and the family can share information about a student’s emotional state at the start and end of the school day will help you both plan the support required accordingly.

Self-regulation refers to the ability to manage one's thoughts, emotions and behaviours to achieve goals and maintain wellbeing. By developing self-regulation skills, students can better manage distractions, overcome obstacles, and control their impulses. This, in turn, can lead to improved academic performance, increased resilience, and enhanced overall wellbeing. To support the development of self-regulation in students, teachers can provide opportunities for developing and improving interoceptive awareness, learning about emotions and emotional expression, and model self-regulatory strategies themselves.

Interoceptive awareness or mindful body awareness activities can be structured into a school day in the morning session, after recess and after lunch to ensure children are ready to learn. These times of transition in the day are also when students are most likely to be dysregulated and struggling to settle. Regularly doing these activities will support children to recognise, understand and manage their emotions at school and develop self-regulation.

Find a range of interoception activities for the early years, and more information on how to implement these into classrooms in the Student Wellbeing Hub's Brain Break Bops and Get ready to learn resources.

The following are general strategies only – they may not be suitable responses for all students in all circumstances.

- Allow for unscheduled time during the day for the student to take a break, allowing them to do something they are interested in and that makes them feel calm, safe and happy. Breaks in themselves provide a distraction, which may be enough to support students to calm down. However, if students are highly stressed or in panic mode, a break may not be enough to allow them to neurologically and biologically calm down.

- Provide a quiet and calm space for the student to retreat to that is their ‘safe space’ (noting that the student should be visible to you at all times).

- Encourage sensory regulation activities such as wearing headphones, deep breathing, stretching, stimming or fidgeting.

- Encourage physical activity, such as going for a walk or playing outside.

- Create a visual schedule or countdown to help the child understand when a break is coming.

- Give them some time and space to relax, limiting conversation and interactions from others as much as possible.

Featured videos

Understanding neurodiversity and autism

Using social stories with your students: Video

Understanding emotions and behaviour of autistic children: Video

Family resource

Starting School